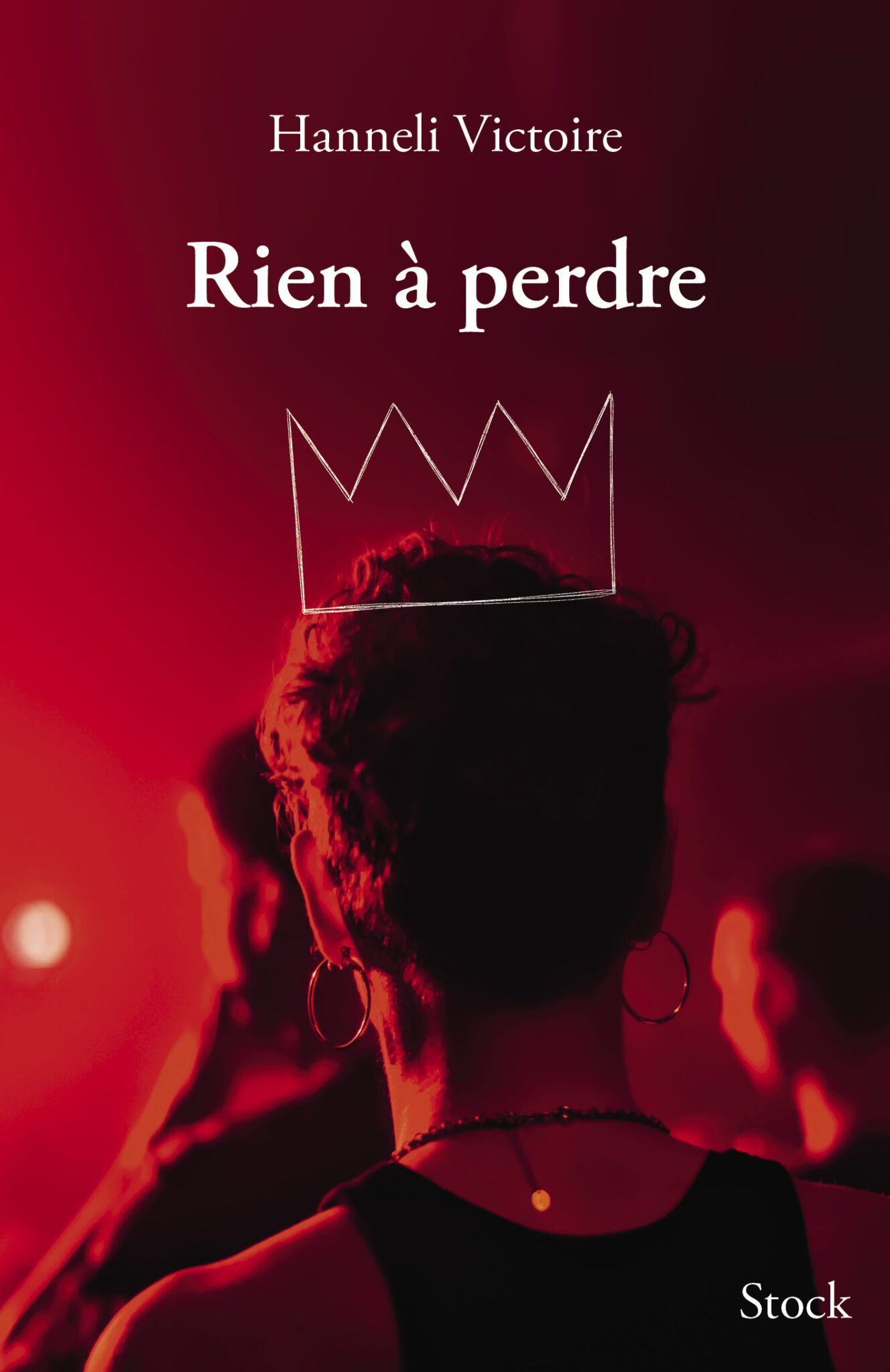

It’s a love story like there are already millions in literature. Except that Hanneli Victoire is inspired by her life as a young transmasculine who still doesn’t admit it and understands it through her encounters within the LGBTI + community. An initiatory journey populated by questions of expression and gender identity, sexuality, social classes, social networks and militant commitments to be placed in the hands of everyone, especially those who know nothing about transidentity issues. However, Hanneli Victoire never falls into voyeurism or heavy pedagogy, and instead uses her incisive and ultra-accessible style to tell the banality of the pain of loving.. Especially when you are trans, young, ultra-connected and committed, as the author tells us in an interview, following the publication on February 1, 2023 by Stock editions of his autofiction. With Hanneli Victoire we talked about queer love, trans representation and tenderness.

Interview with Hanneli Victoire, author of Nothing to Lose

To miss. How do you introduce yourself?

Hannel Victoria. I am Hanneli Victoire, journalist and now writer, monomaniac with Gaga, Mylène and Céline and everything that is discredited, because it is too feminine, by legitimate culture.

How autobiographical is Nothing to Lose? Why did you choose autofiction?

Everything in this novel happened in real life and the narrator is my fictional double. Later, I built a plot and characters from my memories, sometimes having to make chronological arrangements, accentuate character traits and focus on only a few points. I chose autofiction because it seemed like good material to develop a story that I wanted to write and that I think will speak to a lot of people.

The book opens with you, in the midst of gender dysphoria, not wanting to “play this game of being a girl” anymore. Has choosing a gender-neutral expression brought you any kind of relief in a sexist and patriarchal society like ours?

This is indeed a central question in the text. Stopping by the norms of heteronormativity, especially in terms of seduction, has allowed me to liberate my body, in every sense of the word. By ceasing to wear make-up, hair or even tight-fitting clothes, it freed up my movements and made me discover the features of my face, without artifice. We can then focus on something else.

Later you also write: “I don’t want to look like a girl anymore. I don’t want any more coercion. I don’t want to feel in danger anymore […], I’m not a girl, I’m invincible. Do you think that if society was less sexist, we would accept more fluid, less binary identities?

Oh yeah, really! There would always be people who would like to identify with one gender rather than another, but the spectrum would be much more open and the potential for thinking of oneself, of oneself and of one’s body, intimately, as in public space, much wider. .

You write that in the provinces “you are born, you live, you die, without asking complicated questions, unless you are a fag, and you have to leave in order not to die”: in your opinion, why the exodus from the countryside to the cities are so common among LGBTI+ people?

I think it is above all a question of representation. In the countryside, norms of gender and sexuality are no stronger than in cities, but more confined to a given territory within a smaller population, and inevitably more exacerbated. Not matching it means for many having to find models elsewhere. Finding peers is very important in the search for identity, to live lives that resemble us, in terms of love, friendship, culture or sexuality.

She also testifies with great tenderness that she was a “queer girl”: to what extent could this have been a stage in your personal transition?

I enjoyed being a FAP. Really, gays have been my gateway to so many things. The relationship with seduction, with virility, with fashion, with body standards, with culture, I identified with it a lot. Being with them allowed me to find my own path and gave me role models of men I wanted to be like, away from the fixed masculinity of heterosexuals.

Write about how artist Chris paved the way for you: Why is it important to have LGBTI+ icons that can serve as representation to facilitate screenings? Do you think you would have stopped by later if you hadn’t identified with Chris’ trans journey?

I don’t know if I would have moved on later, I think Chris’ second album was able to accentuate something that I had already been maturing in me for a long time. However, I had never met trans or transmasc men before dating one. I believe that if I had role models of trans people on TV or in culture, who assume their trans identity and are both accomplished and confident, that yes, it would have helped me younger, I would have been less prejudiced, and most importantly I would have been less fearful.

Choose in your book to write in black and white the way you misrepresented your first love, Eli, before being corrected: is it your desire to do pedagogy through your book?

I have chosen to tell this passage, because it illustrates very well all the confusion that people who know nothing about transidentity can experience, but it also shows that attraction can’t be chosen, when you think you’re falling in love with someone it turns out to be someone else, and I find that very beautiful.

Beyond the issue of transidentity, your book is also a very contemporary novel about love and the loss of love. Do you think it is more difficult to break today in the age of social networks?

I think so, but I think it’s also very queer related. It doesn’t matter if we’re in a big city or a small town, we always feel like we’re twelve years old in this community, and that we’ll always run into our exes. With social networks this fear multiplies, given that we can also meet in the virtual space through stories or posts. What hell [rires] !

Precisely, write: “To talk about queer love is to protect under the same umbrella both our experiences, our traumas, our sexualities, our rejections, our complicity […]. Queer love is like all the others, formatted, and above all it hits harder because it is lived on the margins. » Are our queer loves lived more intensely, but also potentially more violent because we are marginalized people, therefore more subject to social violence, in your opinion?

Certain. LGBTIphobia destroys us in our privacy and induces totally exacerbated relationships with violence, danger and fear. I think this partly explains the general poignancy of many relationships, which are humorously caricatured, yet reveal profound ambiguities.

“The donkey is, in our collective history, at the heart of our struggles […]. The donkey is the latest transgression, the sacred sin, the one with which our identities have always been demonized. […] Rather than enjoying shame, we should enjoy pride”: how can non-standard sex be a weapon of political dissent, in your opinion?

It is one of the strongest taboos of our contemporary society. Everyone talks about it, but no one wants to admit their desires when it comes to desires outside the regime of heterosexuality. Queer practices or even abstinence are in themselves ways to break the dominant narrative.

“The new generation is here and the trench warfare of intersectionality has begun. We don’t have many weapons to fight on our scale, apart from a moralizing gaze imbued with a militant purity that exasperates, our inequalities and our egos, enormous thanks to social networks. »: In your opinion, how can the pursuit of militant purity be harmful?

The main pitfall for me is the lack of a clear political goal. Wanting the end of patriarchy cannot be a slogan in itself, militant projects are needed that are more rooted in social problems, with concrete levers of action and quantifiable results. It can be negotiated in many ways, such as an ambitious public policy on gender-based and sexual violence, better assistance for LGBTQIA+ students at school, a truly MAP for all… In short, clear demands, which identify both its allies and his detractors. This is the second negative point for me, with militant purity, everyone becomes an enemy, while the goal of activism is the same to change society for everyone.

After the publication of this book which ends on déconfinement, today, when you look in the mirror, what do you see?

I see someone much calmer, more loving, more confident and also tender. I love.

See this post on Instagram

Front page photo credit: Hanneli Victoire photographed by Zoé Chauvet.

More articles about

Rights of LGBTQI+ people

-

Transphobia: 5 key dates to understand the controversies around JK Rowling, from 2018 to 2023

-

Mascare: “Cabaret is an art that is not limited to one genre”

-

Recommended for girls and boys, the papilloma virus vaccine is still avoided in France

-

Why a law for trans people in Scotland was rejected by the UK

-

A feminist masterpiece about transgenderism, Joyland is the best film to see this week

Source: Madmoizelle

Mary Crossley is an author at “The Fashion Vibes”. She is a seasoned journalist who is dedicated to delivering the latest news to her readers. With a keen sense of what’s important, Mary covers a wide range of topics, from politics to lifestyle and everything in between.