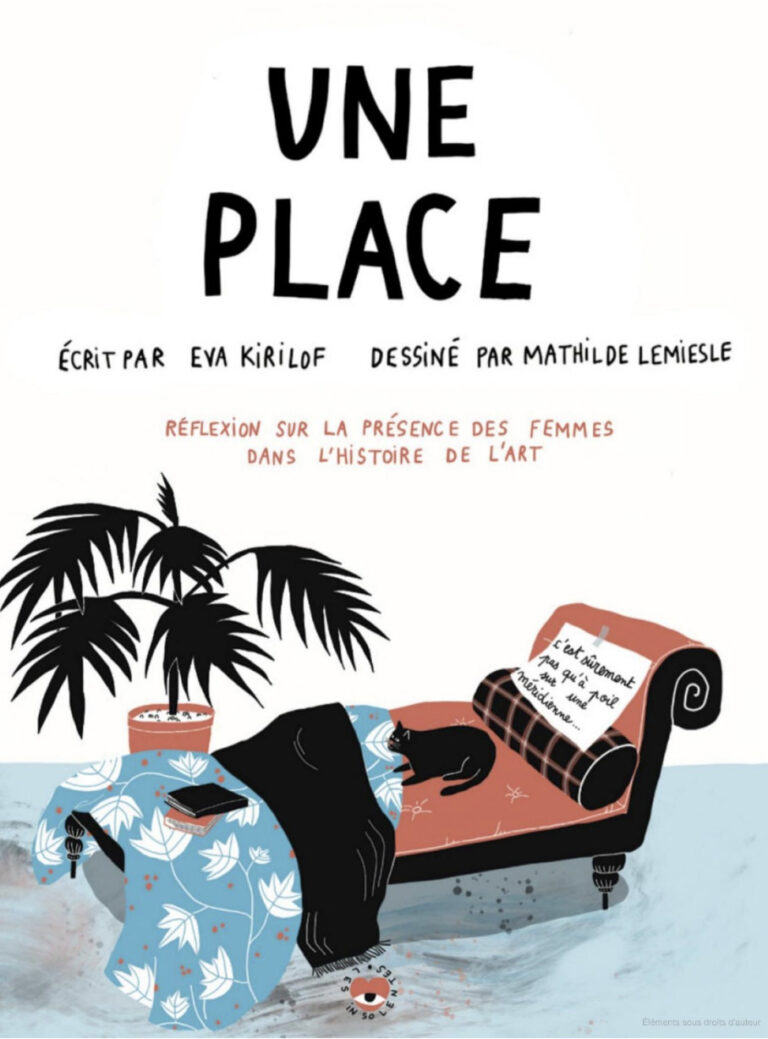

Might make a nice Christmas present for your reactive old uncle, who swears every year that women have never mattered in history in general. A square, written by Eva Kirilof (author of the La Superbe newsletter) and richly illustrated by Mathilde Lemiesle is an important essay that tries to explain in a very simple way how women artists have been ostracized from the history of art for so long, and how, for decades, cultural institutions and university courses have tried to make us believe that they simply never existed. Instead, it is quite the opposite, and this book, which is also a beautiful object, proves it to us, if it were still necessary to do so.

We need to make these women artists family members and not exceptions.

Eva Kiriloff

Interview with Eva Kiriloff

To miss. How did the desire to write Une Place come about?

Eva Kirilof. A square was born from my meeting with Mathilde Lemiesle, who illustrated the book. He had been following my work for a while via my newsletter The superb and Instagram, and suggested they collaborate together. The book had been in the works in my mind for a while, but I was waiting for an opportunity to offer something different before daring to leap. The illustrated format seduced me, because I had never seen graphic essays on this subject.

Once you start scratching, you realize very quickly that there have been a lot of female artists.

Eva Kiriloff

When did you realize that art history had almost ostracized women?

Very late. Too late. I didn’t ask myself the question of the non-presence of women in the history of art during my studies. If the university professors, for me the highest authority at the time, didn’t talk about it or very little, it’s because the question didn’t arise. Same for the museums. If the scientific institutions specializing in these subjects have shown few or few, it is because in the end there have certainly been few. My trust in institutions is ultimately what delayed this realization. The arrival of motherhood into my life has clearly awakened my feminism and with it the desire to immerse myself in the history of art through the prism of gender. Because obviously, once you start scratching, you realize very quickly that there have been a lot of female artists.

In summary, how to explain that women artists have been sidelined for so long?

There is this very tenacious idea that women belong above all to the private and domestic sphere. That this is where their destinies are played out. This is obviously a way to dominate them, and to do so, the capitalist patriarchal society in which we evolve has kept them on the periphery of many fields such as that of art history. Our iconography, our cultural history and, more generally, our collective imagination had to be created by men to continue to maintain their hegemony. Despite numerous pitfalls (such as lack of access to an art education exactly like men before the early 20th century, paid private tuition, lack of access to competitions, nude models, not to mention environmental sexism ) many women, although often white and from privileged backgrounds, have been recognized as artists who have lived on their art for centuries. We will have to wait for the social movements for women’s rights, but also for the second wave of American feminism to be able to talk about it. Since the 1970s, feminist art historians have sought to rehabilitate them, to reintroduce them into big history. But as often it takes time and a lot of patience, because our society still finds it hard to think of the history of art outside the “geniuses” it created.

It is not an oversight that women are underrepresented in museums, galleries, auction rooms, but the result of a system designed not to include them. This is what I’m trying to demonstrate in Une Place.

Eva Kiriloff

We seem to be experiencing a period of “rediscovery” of many female artists, who are brought to light through major exhibitions, books… What should we think of this mea culpa of institutions? Is it timely or is it mostly a marketing issue?

I think since the #MeToo movement, there is now an interest in more equality in the arts. The lines have been moving for the longest time in the Anglo-Saxon world, which does the job of introducing works by women into the permanent collections of museums (the cases of the Tate Modern and Tate Britain are incredible) it offers many monograph exhibitions by women artists, essential for creating knowledge around to them. On the French-speaking side, I see things moving more slowly, we stick to a “catalogue” format of female artists, both in terms of exhibitions and books. It is a format that was needed 50 years ago, I am thinking in particular of the 1976 exhibition “Women Artists: 1550-1950” curated by the historians Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris, but in my opinion, today, we can go further by proposing monographic exhibitions and above all by including women in permanent exhibitions. This is what will establish their presence in museums in the long run. I don’t think it’s a my fault institutions, we’re going to have to go further for that, because obviously the public isn’t fooled, it’s the long-term change we want. But for the moment they respond to a public interest, to a change in progress and with which these institutions want to be associated. We’ll have to see how they transform the test. For the fashion phenomenon and the marketing coup, I say all the better if needed definitely make these artists known, but clearly at some point you will have to position yourself and understand the limitations of this model, which also contributes to their ostracism. Personally, I don’t think that continuing to make women artists talk to each other exclusively, as if they hadn’t evolved in a world of men, will lead us to where we would like to be.

What concretely and truly remains to be done to give the light that women artists in the history of art deserve?

The director of the Tate Modern in London, Frances Morris, said a sentence that seems essential to me: “Familiarity breeds authority. People like what they know. » We need to make these women artists family members and not exceptions. We must rethink so-called feminist curatorial practices, which include many often essentializing prejudices, we must perpetuate their presence in school and university curricula, in the permanent collections of museums, freeing up money for research, an often precarious and essential profession. we can create knowledge around these artists, for the restoration and conservation of their works. Then, also, questioning ourselves globally, understand that it is not an oversight that women are underrepresented in museums, galleries, auction rooms (although I have seen that things have been moving a lot lately also in that part) but the result of a system designed not to include They. This is what I’m trying to prove A square.

In your book you talk about many women. Which would you choose if you only had to invite us to discover some of them?

It’s true that my goal was not to introduce new artists through the book, but I was very happy to include the Portuguese artist Paula Rego who is perhaps one of the artists that fascinates me the most. Also Janet Sobel, because I think I’m increasingly drawn to self-taughts, and finally maybe Mierle Laderman Ukeles, because she helps politicize motherhood.

Source: Madmoizelle

Elizabeth Cabrera is an author and journalist who writes for The Fashion Vibes. With a talent for staying up-to-date on the latest news and trends, Elizabeth is dedicated to delivering informative and engaging articles that keep readers informed on the latest developments.