Nicholas Philibert, whose film On the Adamante won the Golden Bear at the 73rd Berlinale on Saturday, has devoted his life to observational documentary film, alternating between interviews and long, patient recordings of his subjects and following what they do. The most famous of these is Etre et Avoir (2002), which followed a year in the life of a tiny rural school where the only teacher – friendly but demanding in the French way – taught several classes at the same time. Thanks to this dedicated teacher’s appeal—and its delights Childrenof course – Etre et Avoir became an unlikely but enduring art house hit.

Philibert also keeps a close eye on student nurses, a day in the life of a radio station and a night in an urban menagerie. As far as I can remember, he never turns up himself – although this is not a reliable memory since he has been plowing those furrows since 1978 – but his presence is felt as a guiding sensibility. These are films that together form a humanist project, even if he only makes it explicit in appropriate quotes that introduce each film and tell short afterwords about where we happen to add a few comments about what makes it so valuable that They wish we heard more about him off

In On the Adamante, we are on a psychiatric hospital houseboat, bobbing reassuringly on the Seine. Built specifically for day patients in 2019, the boat is made of wood with large shuttered windows and decks covered with potted plants. Inside there are spaces for workshops and courses – art, music, dance, cooking – offered to patients dealing with a wide variety of many different pathologies. A young man looks intently below the camera’s eyeline as he describes how he gets upset by other people’s noise. Frederic, an older but boisterous bohemian, talks straight about art before sharing that he and his brother are reincarnations of Vincent van Gogh and his brother Theo. A plump, middle-aged man recalls being told by a police officer that if he actually killed someone, he would go to prison for 30 years. Luckily he didn’t have a gun then, he thought.

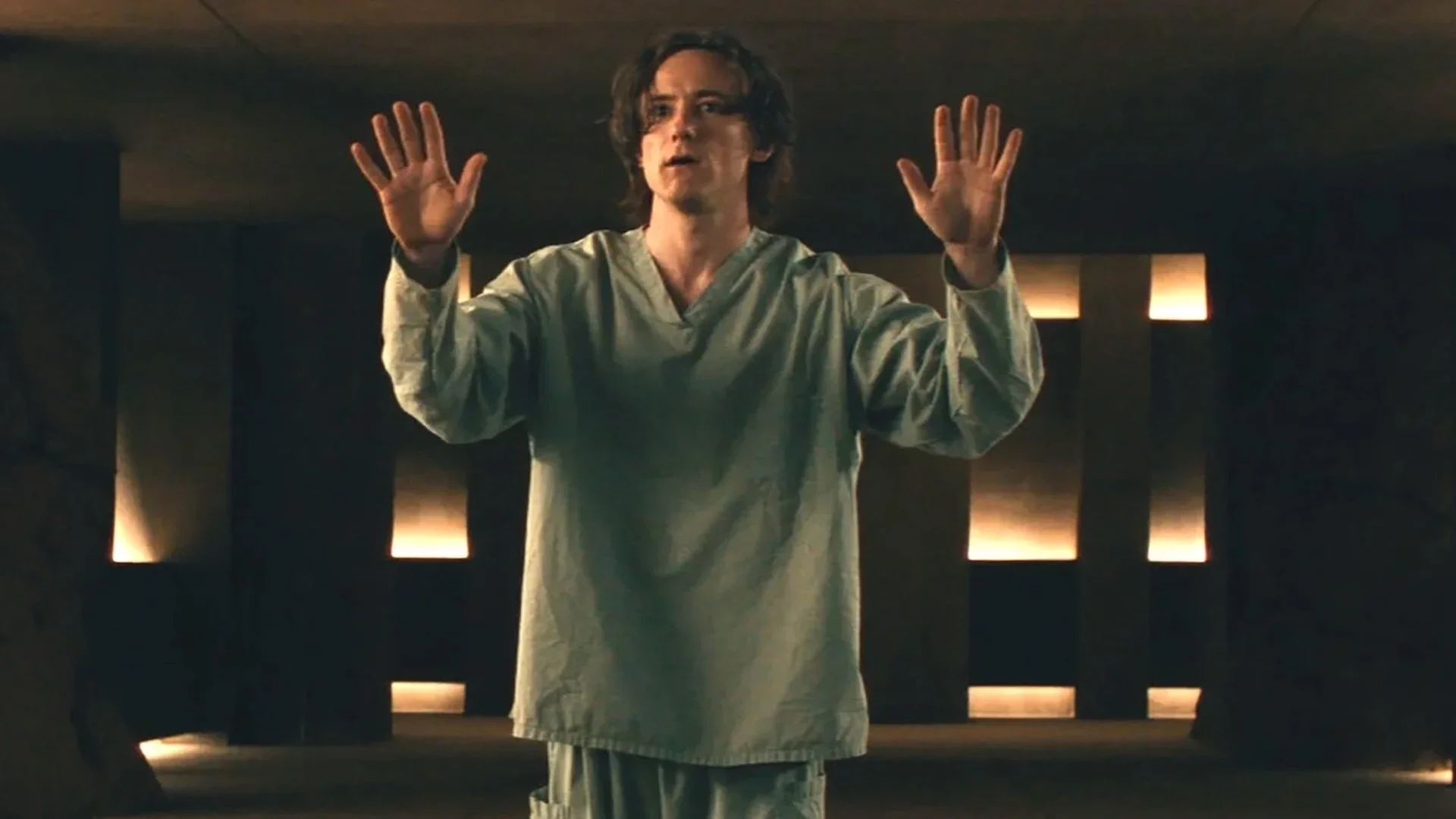

So one is autistic, the other delusional, the last paranoid. Maybe, maybe not. Philibert does not diagnose or assign labels. Why would he if the patients had their own much more mundane descriptions of their ailments? “If I didn’t have my medication. I’m starting to get angry,” says Francois, “I think I’m Jesus surrounded by birds.” He has been sick, he says, since he was 18. “And now I’m sick,” he says firmly. A melancholic African woman remembers that her son was placed in a foster family when he was 5 years old. He is now 16. Once a month she visits him with a social worker. “It’s better now,” she says. “When I went to see him, I couldn’t get a word out at first.”

The activities range from sewing and making jam to keeping the books for the coffee bar, which the patients do themselves. Balancing these accounts takes time and often struggle, but time is all everyone has here. After their art sessions, they show each other their work and discuss at length what they tried to do. The film club, which has been in existence for 10 years, is planning a film festival with classic films such as Fellini’s 8½ and one of Jack London’s adaptations white tusk.

Not everyone we see is talking – some are gloomy, one can only be seen on the boat’s deck spinning endlessly in time to a private dance score – but the customers here, even the toothless ones, seem to be spending a lot of time has been on the street for several years, possibly including last night, is exceptionally artistic. In his concluding remarks, Philibert suggests that there must be places in the world that have room for poetry. Poetry definitely comes first on the good ship Adamant.

It seems unlikely that they are some random bunch of mentally ill people. Since Philibert has no educational conversations with the professionals, he obviously cannot spend too much time with people who cannot communicate or who are more disturbed. The cast is also essentially self-selected: it makes sense that those who want to perform for the film will be the natural performers who already sing and recite their own poetry. And of course he wants us there. His technique depends entirely on our response to his motives for success, so he wants to find those with the best stories.

But for all the decency and attractiveness of his film, the people on this beautiful hospital boat are ultimately not as attractive as the children in the one-room school. Rather, these are people you can dodge in one go, and that might be the point. We share a carriage with them for a few hours and find them fascinating, complex and often funny. They wish them all and their beautiful wooden boat every success. But in the end I was relieved to realize that we had reached the finish line. I was looking forward to getting out.

Source: Deadline

Elizabeth Cabrera is an author and journalist who writes for The Fashion Vibes. With a talent for staying up-to-date on the latest news and trends, Elizabeth is dedicated to delivering informative and engaging articles that keep readers informed on the latest developments.