Jennifer Dazal, author of Curious Art, says art history doesn’t have to be boring. The strangest, funniest, most fascinating stories” (“Bombora”), hidden behind great artists and their masterpieces. The author assures you that even if you fell asleep in art classes at school or university, that doesn’t mean you don’t like painting at all.

It all depends on the presentation of the material: if it is dry enough, of course, this will not add interest to museums and exhibitions.

Jennifer Dazal has been curating the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh (USA) for many years, and most of all she loves people who come to her with a hatred for anything painting. He was once like that, but over time he changed his views – he began to study art, started his own podcast ArtCurious, where he explains to everyone in an accessible form what this or that direction means, causing thousands of people to fall for it. love with material presentation.

In the new book, Dazal continues to do just that, telling readers how exciting the art world can be. Some facts from the publication are given in our material.

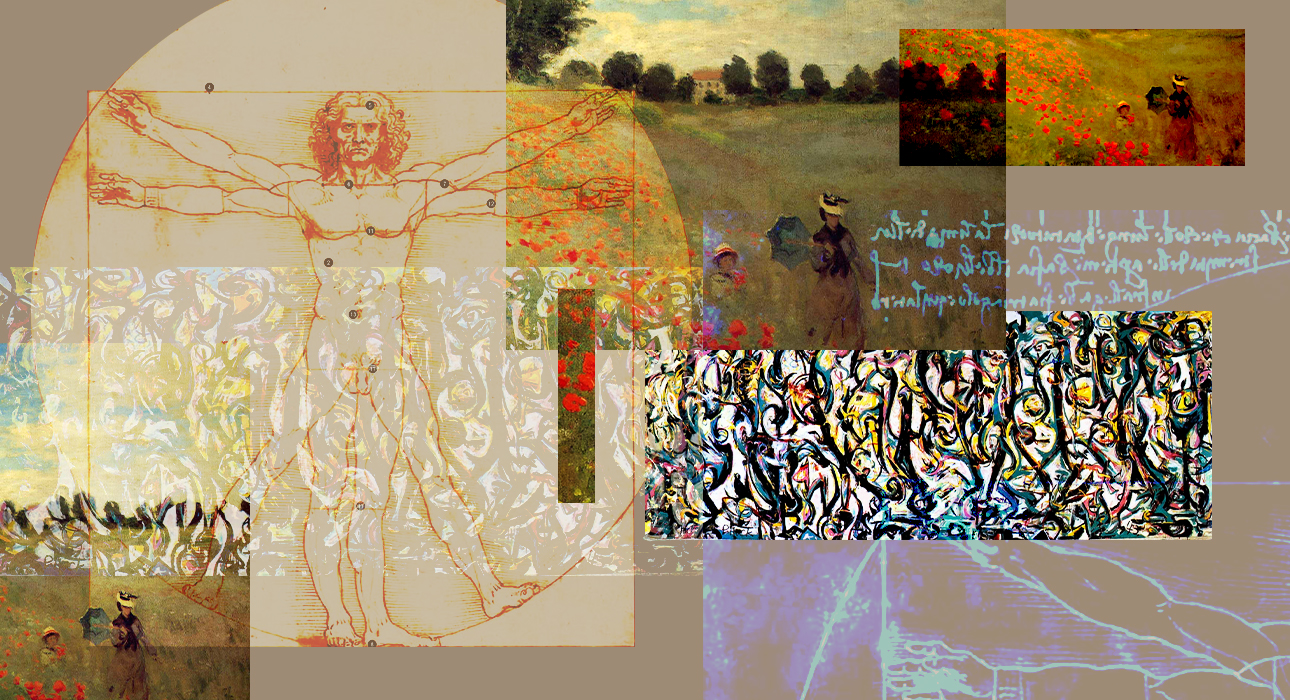

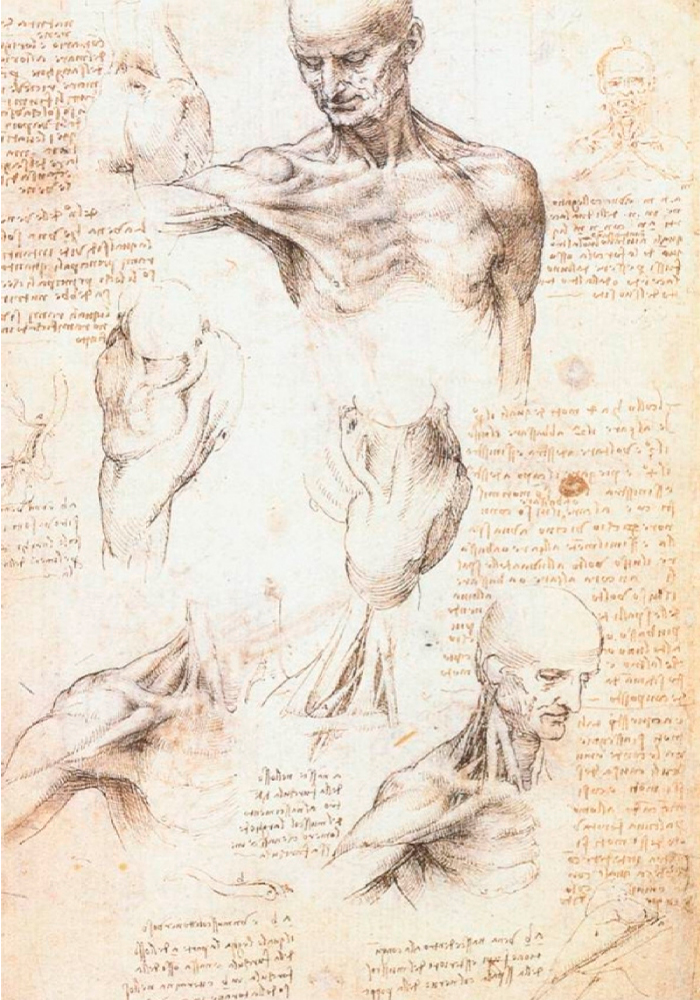

anatomy lover

It was hard enough to dispel the myths that Leonardo, Michelangelo, and their colleagues in the trade were secretly stealing bodies. Some of these myths have proven true. No, the artists did not deliberately abduct the dead, but hired doctors to study the human body and then depicted it on their canvas.

Thus, Andreas Vesalius, a professor of anatomy at the University of Padua, stated that he signed an agreement with the famous Venetian artist Titian and later allowed Vesalius to assist in autopsies in exchange for medical illustrations that would appear in his books.

The most famous Renaissance depictions of the human body belong to Leonardo da Vinci. Countless anatomical drawings of Leonardo are constantly found in the codes – diaries and notebooks, which he kept throughout his life. And they were revolutionary for their time. Like an architect, Leonardo depicted each part of the human body from different perspectives. Given how detailed these sketches were, the artist not only studied bodies but also did extensive research, and it’s quite possible that there was more than one: Carmen Bambac, curator of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, suggests: Leonardo, in aid, and Pavia He created the most detailed illustrations under the guidance of Marcantonio della Torre, a young professor from his University.

Through him, Leonardo gained access to corpses and created his anatomical works in collaboration with him.

But the interesting thing is that Leonardo’s medical drawings were not published during his lifetime; It is also unknown whether della Torre would use them for scientific or educational purposes, as his life was shortened by the plague.

Leonardo himself also did not attempt to show della Torre’s drawings to the masses after his death, but the fact that these drawings were made in the artist’s notebooks indicates that they were intended for personal use, to quench Leonardo’s eternal thirst for knowledge and curiosity. as well as to improve their artistic skills.

riot without cause

Few people know that the favorite artist of mothers and grandmothers, who draws flowers and landscapes, actually has a violent temper. The future god of Impressionism was born in Paris in 1840, but spent most of his childhood in Le Havre, a port town 200 kilometers northwest of Paris. Like many artists, Monet showed his talent early, drawing cartoons of his classmates in textbooks. The punishment did not suit him. Later, the artist admitted: “Even as a child, they could not force me to follow the rules.” He did the same at home.

The head of the Monet family, Adolf, was not enthusiastic about art – he was an entrepreneur (the essence of his activities is still not entirely clear) and hoped that his son would follow in his footsteps. However, young Monet had very different plans – he wanted to become an artist. Fortunately, Madame Monet, Louise, sided with her son. He was a fan of the arts and therefore organized his son’s education on drawing until his death in 1857.

In the same year, Claude met Eugene Boudin, a well-known artist whose method of work is different from the generally accepted – he painted on the street, in the fresh air! It was quite radical and even a little strange, since most artists would simply draw on the street and then work in specially designated studios or other art spaces with all the necessary tools. But not Boudin. He initiated the young Monet into his method of work, in which an entire painting was created outdoors. But more importantly, Boudin confirmed what Monet was slowly beginning to realize: He wanted to make it his life’s work. Later, Claude moved to Paris. As far as we remember, in spite of the father against it (this is another manifestation of a rebellious character!).

Well, what happened next, many probably remember from the history books – Claude Monet began to attend the Paris Salon, one of the most prestigious exhibitions in France, then left the Salon, entered the university at the Faculty of Arts, quickly disappointed. his work left the walls of the institution and he met Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley and Frédéric Bazille. They had similar views on life and painting. Joining the Anonymous Society, they organized their first exhibition in Boulevard des Capucines, which went down in history as an exhibition of the Impressionists.

As Impressionism grew in popularity, the once close-knit group began to disintegrate. With enough money and a good standing in the art world, Monet gradually began to distance himself from his Impressionist friends and develop his own style and themes, which amounted to creating a series of canvases depicting the same scene at different times of the day and under. different weather conditions.

Before the fifth exhibition of the Anonymous Society in 1880, Monet shocked everyone by his refusal to attend and his decision to submit works to the Paris Salon. He made his decision directly and openly, violating the founding rule of his own society, and never looked back. This can be facilitated by the acceptance of one of his works for display at the Salon. But the decision had negative consequences: other impressionists were offended and stopped friendly relations with him.

Claude didn’t care: he was already very famous in those days and had already stepped out of the shadows of his friends. Over the next 20 years, Claude Monet became so well known and famous that the newspaper Le Temps published his autobiography, a history of his artistic development, exactly 26 years before his death. In this article, Monet gracefully confirmed the rumors about his rebellious path and even graced his biography in places. So what? Genius can do anything!

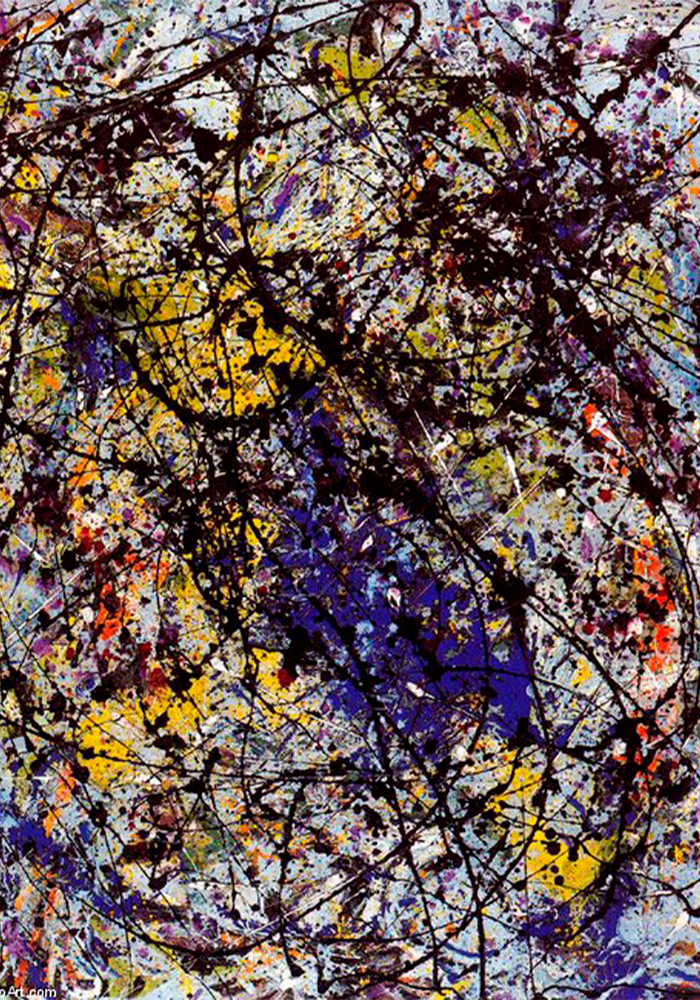

The CIA and the Abstract Expressionists

The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) funded art, namely the work of revolutionary artists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, to counter the USSR in the Cold War. This is not a conspiracy theory, it’s a fact.

When US President Harry Truman founded the CIA in September 1947, one of the CIA’s divisions known as the Propaganda Media Division was tasked with instilling the right mindset in the world’s smartest people. This was not easy, especially given the fact that many influential writers, critics, artists, musicians and philosophers, both in America and Europe, found certain principles of communism (its egalitarian basis) quite appealing. And since many of these people immigrated to the United States during World War II, the intelligentsia worried that they would bring their communism with them.

Before the propaganda media department, there was a prime example (and warning) in the US State Department. A little while ago, in 1946, the State Department held a large exhibition to openly demonstrate the cultural superiority of the United States.

The Advancement of American Art was sponsored by the State Department for $49,000. The money was spent on the purchase of 79 paintings by famous artists of the time: Georgia O’Keeffe, Romare Bearden, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Jacob Lawrence and others. Talent was not the only criterion for selecting artists; Another important aspect was diversity, an important aspect of American excellence.

After its premiere at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the exhibition was split in two and sent to different parts of the world – and it failed miserably. Viewers just didn’t like the photos. They were works of art about the life of that time – about cities, about endless noise, communities of color and social change. Ordinary people could not stand it, neither could politicians.

Therefore, a new task arose before the special department of the CIA – to promote artists in a completely different direction. The choice fell on representatives of abstract expressionism.

Compared to their American Art Advancement counterparts, the Abstract Expressionists seemed wild and even somewhat anarchic, and their work was not widely known outside of a narrow circle of artists and researchers. However, it is worth remembering what goals the CIA pursued: they needed art that was a reflection of advanced thinking and an advanced civilization built on freedom of expression. And abstract expressionism was truly art for the sake of art.

The most likely outcome of government support for abstract expressionism was the lifetime recognition and renown of these writers – and this is far from being a prize for all innovative artists. The worldwide fame of this direction has significantly accelerated the recognition of contemporary art by reputable institutions. After all, just a year after Jackson Pollock died in a car accident in 1956, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (the most respected of institutions!) purchased his iconic painting “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” for $30,000. For the art world of that time – an unheard of amount!

Source: People Talk