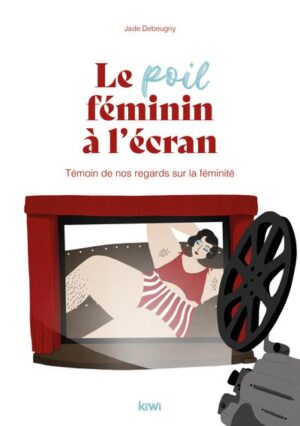

But where is our hair? That’s what you wonder every time you watch a razor commercial, where women shave a perfectly smooth calf. But also films or series in which the heroines invariably have hairless bodies. Much like period blood, body hair is part of the behind-the-scenes femininity we’ve been taught to disguise, even consider dirty or shameful. Of course, things are changing under the influence of personalities who dare to wear them in broad daylight, such as models Mara Lafontan, Emily Ratajkowski or activist Esther Calixte-Bea. But the virulence of the reactions they elicit clearly indicates that there is still a long way to go. And that the issue of body hair is anything but trivial. Based on this observation, the young director and screenwriter Jade Debeugny became interested in the question of the representation of our body hair in cinema, delivering a fascinating essay, Female hair on screen which has just been released by Kiwi Editions.

Interview with Jade Debeugny, author of “Female hair on screen”

Only the hair focuses how the injunctions on our bodies are so standardized and internalized that they become almost invisible.

Jade Debugny

To miss. Why this interest in hair?

Jade Debugny. This book is the culmination of an entire process. Intimate first, since from the moment my hair appeared, I’ve been worked up by this question like many teenagers elsewhere. From the age of 12 I wanted to shave them, we talked about them with my friends and I lived in fear that we would see them. For years I was not surprised that all the women around me, like in magazines, waxed. It was the norm. And then around 18, when I was starting my film studies, I started thinking about feminism issues, to raise awareness of sexism. I understood that the relationship we have with our hair is not trivial. This argument may seem anecdotal, even unusual, but it is actually very significant. Only the hair focuses how the injunctions on our bodies are so standardized and internalized that they become almost invisible.

What does hair say with its presence or rather its absence on the screen about society’s relationship with our femininity?

I’ll start with a very eloquent example. This is the reception of director Rachel Lang’s feature debut, Baden-Baden. In this film, the heroine has her hair under her arms. It’s just a character detail about her like her long or short hair and she’s absolutely not the subject of the plot. But her actress, Salomé Richard, told me how some critics focused on it, talking more about it than about the film as such. She the latter has also been perceived as a feminist since showing her hair has become a militant act. However, what is crazy is that hair wasn’t militant per se in the beginning, it became so because our society discriminated against it for women – and people it perceives as such – and we decided that it shouldn’t exist on our bodies. Hairlessness is so deeply ingrained in us that a hairy woman’s armpit or pubis is conspicuous and often shocks the eye. The content on our screens highlights the absurdity of the situation: the removal of something that is part of the human body has become a banality when it is its absence that could challenge us.

In your book you also explain that the representation of hair is intimately linked to the notion of male gauze (editor’s note, a concept theorized by director Laura Mulvey in 1975 which roughly indicates how visual culture imposes a heterosexual male perspective)…

Yes, because the absence of hair is one of the elements that participates in the standardized aesthetics of female bodies that we have seen a lot at work, especially in the cinema. Women naturally appear hairless. And even when the hair is present, which is very rare, its diversity, evolution and possibilities are not taken into consideration. We never see what it’s like to live with our hair, yet we all do, whether we shave or not.. As if we don’t have to reveal the underside of “femininity” and that we just want to show “out-of-the-box” women. I especially think of Adele ‘s life by Abdellatif Kechiche, often cited for his appearance ” male gauze “. The constant lack of hair of the two actresses seems to me a costume that participates in the aestheticization of their bodies and their sexuality. On the contrary, we are also witnessing the emergence of a female gauzetheorized by Iris Brey, in her book The female gaze, a revolution on the screen. It’s a way of filming women without turning them into objects, retranslating the singularity of the character and not just observing them. The film fuck me, by Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi fits, for example, into this perspective. And we see characters with different hairs shaving, discussing the topic. In short, hair does not appear as a subject in the strict sense, but is tackled without injunctions, as an experience.

What, in your opinion, is the responsibility of the film industry: is it content to reflect the reality of the norm or does it create it?

Both, in my opinion. In my book I give the example of a director friend, Paul, who wondered about the hairiness of his female character. Since the latter has evolved into a sports universe, where you have to be in perfection and performance, it seemed logical and believable that the actress was shaved: it serves the purpose of the film beyond even the question of “realism”. As it stands, a film showing shaved women might seem more realistic since we still see little female hair in real life. But there are so many movies where we could afford to change the norm a bit and show women with their hair. The problem is also with the wearer. This can be difficult as the reactions are sometimes virulent. Just see the controversy or the hype when Emily Ratajkowski or Julia Roberts sport hairy armpits. Things change, but injunctions die hard.

Is there a new generation of filmmakers who tend to change points of view and representations?

I particularly admire the work of Céline Sciamma. As much as a director (Noteespecially from Portrait of the girl on fire you hate girl groups) than in his political commitment. I am also thinking, on the side of the actress, of Adèle Haenel. I think the challenge today is not so much to change attitudes as to diversify them. And there’s a whole new generation of young filmmakers who carry that will. For my part, I see them at work a lot in short films, because that’s usually where the profession begins, and there’s often more freedom thanks to the format. I have high hopes that in a few years the looks of this generation will unfold just as much in feature films and that this will change the norm.

Source: Madmoizelle

Elizabeth Cabrera is an author and journalist who writes for The Fashion Vibes. With a talent for staying up-to-date on the latest news and trends, Elizabeth is dedicated to delivering informative and engaging articles that keep readers informed on the latest developments.