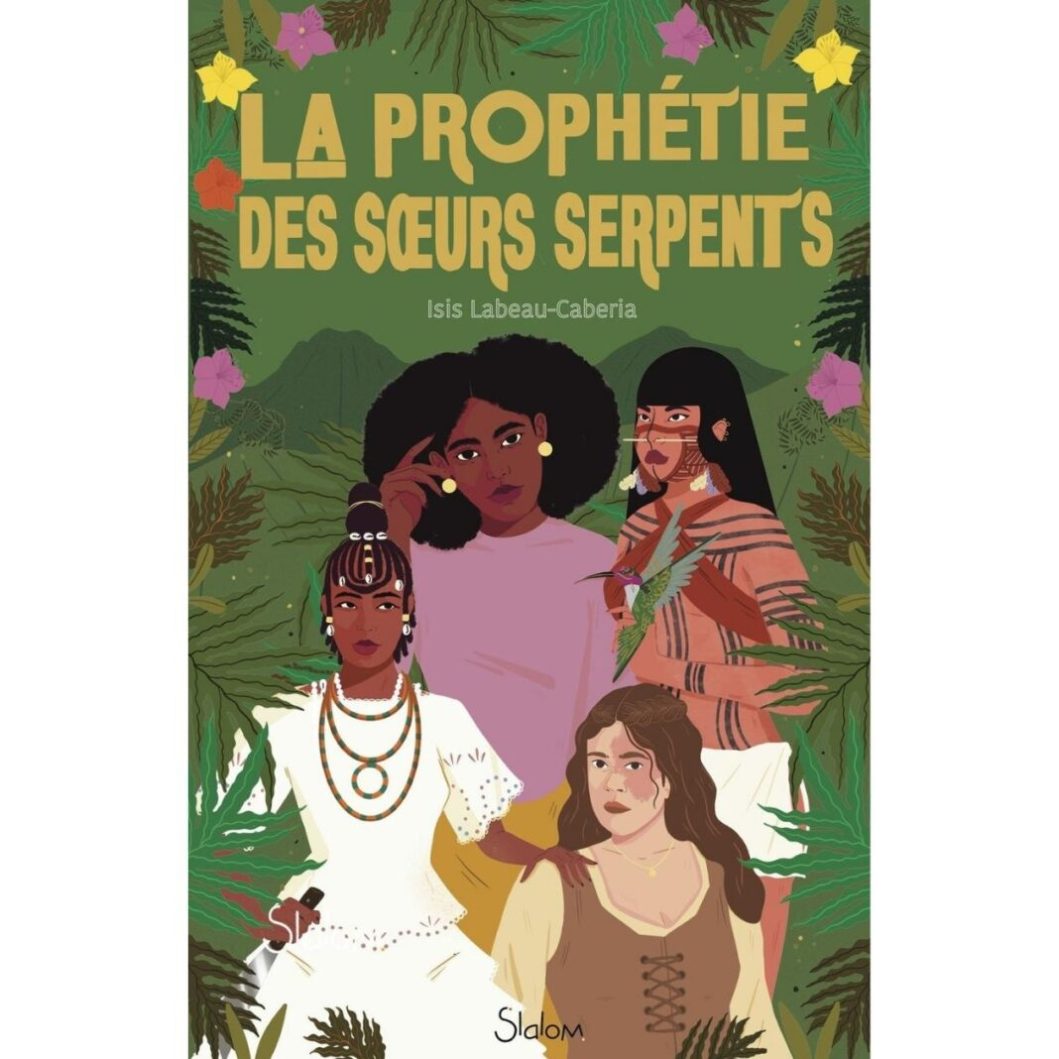

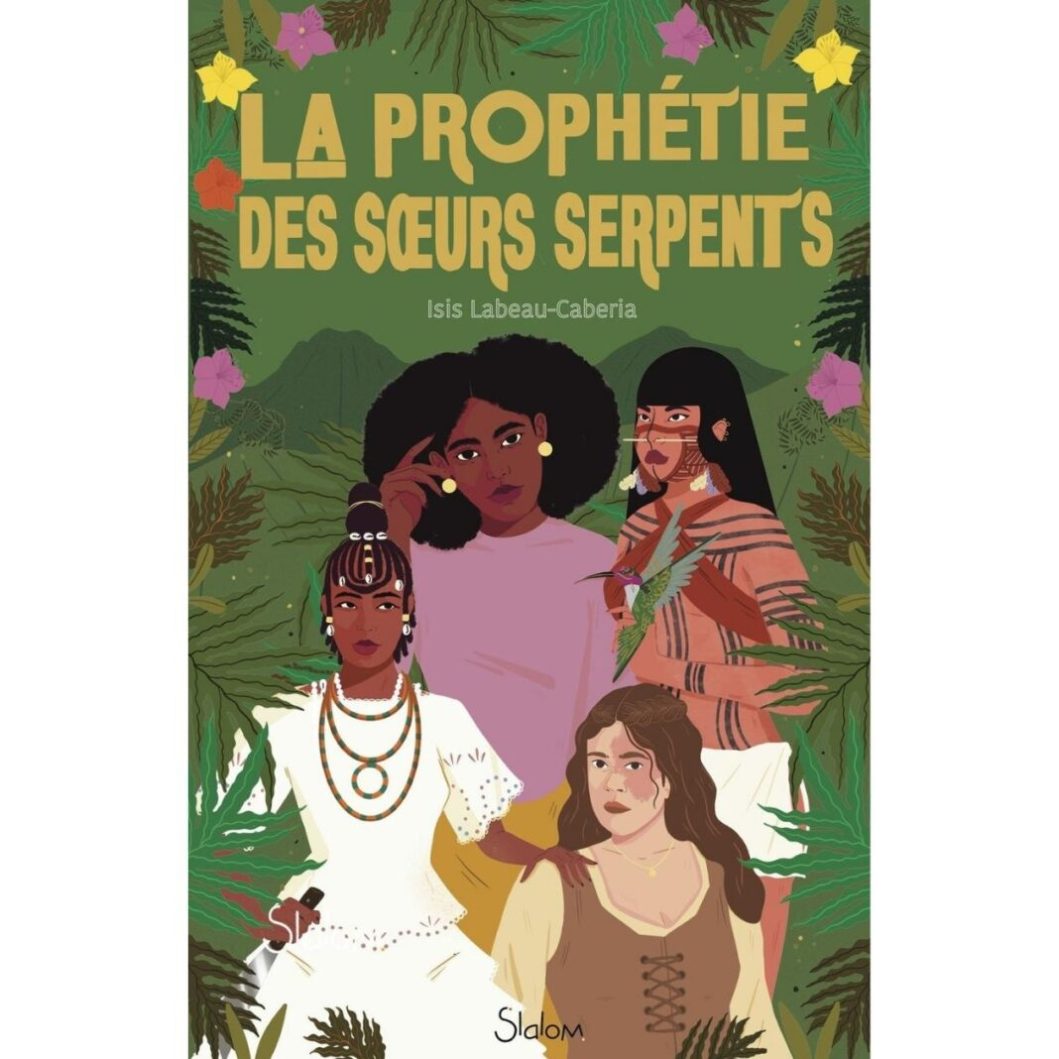

Naïlah is a Parisian teenager and feels uncomfortable with herself. She is getting ready for a boring summer at her grandmother’s house Martinique – a country of which he knows nothing but of which he does not want to know anything. But behind the shot white sand beaches and coconut trees, the young girl does not take long to discover them a tragic reality: that of a land still marked by the scars of colonialism. A ancient family secret will lead you to the traces of ancestral magic and of the history of the island in the 17th century century.

At that moment live Noumyoung shaman kalinago deal with settler violence; Funmilaio, priestess yoruba deported to the island as slave ; And Rozenn, farmer Breton arrived in the colony as a fiancé after being accused of witchcraft.

Gathered by a thousand-year prophecy and a desperate search, the four young women lover of freedom will find out the power of sisterhood in the face of oppression and will attempt, at your own risk, to change the course of history…

If not necessary recommend only one bookwould be The Prophecy of the Serpent Sisters. We have rarely been able to read such a novel exciting, virtuous and powerful. Isis Labeau-Caberia signs a great ecofeminist and decolonial fresco, between three continents and two centuries. The novel is real gold mine in the field of history, imaginative And emotions.

We are witnessing the resurrection of peoples massacred by European settlers, such as the kalinagos, Caribbean natives of the XVIIᵉ century. Parallel to these cultures which Isis Labeau-Caberia shows the richness, the author also pays a vibrant homage to women whose existence has been evaded by dominant historical narratives. By drawing on historical archives but also in his imaginationshe gives them a voice and makes them the protagonists of this extremely generous story in terms of twistsin Magic It’s inside beauty.

Decolonizing History, celebrate feminist and anti-racist strugglesinstill a powerful message of love, of sisterhood And of hope to people who descend from this colonial history still firmly rooted in the present… These are just some of the many reasons The Prophecy of the Serpent Sisters an exciting and sublime novel And necessary.

And for this Lose has decided to give the floor to the most suitable person to talk about it: its author. Isis Labeau-Caberia, 31, is a Martinique author fiction and non-fiction. She explores the question of resistance to slavery and colonialism in different formsas through this first novel, between history and fantastic literature. His podcast The errant Morello cherry it conveys the history of Africa and its diasporas in the Americas and the Caribbean from a decolonial point of view.

To miss. What is the genesis of your novel?

Isis Labeau-Caberia. I wrote this book in less than 6 months because I have carried it in me for years, not to say decades. Combine both my knowledge of historianbut also something of the order of a synthesis of my personal and community experienceas a young man Martiniquan of the 21st century.

I wished articulate the challenges of the presentin particular the question of the decolonial, anti-patriarchal and anti-racist struggle with the long story. I wanted to show that our struggles are part of this history, of this genealogy. Our struggles are those of our predecessors.

I wanted to write an ecofeminist and decolonial fable for our time and for the younger generations.

The novel spans two centuries and three continents. Specifically, how did you organize yourself to write this great fresco?

I started with the themes I wanted to illustrate and the messages I wanted to convey. From there I built the characters. I wanted to write an ecofeminist and decolonial fable for our time and for the younger generations. A novel that is a historical document but who has it a strong imaginary and emotional dimension. Then the characters came to life autonomous way And quite magical. They took me in directions that I hadn’t initially planned at all.

Why did you choose to weave history and imagination?

I had three goals in mind. The first, of course, was pass on this story that is not taught history and school books. We can see that there is a strong demand from the younger generation to have access to a historical account that truly represents us.

The second goal was to show a lot concretely that slavery and colonialism are not just past events which ended in 1848 with the abolition of slavery or in the 1940s with the independence movement. They are systems that continue to exist and affect our lives in the present.

In the end I wanted return tribute. I consider this novel as a love letterboth at ns predecessorsthese ancestorsthese little women who have been at the crossroads of so much violence. In the face of dehumanization, they never gave up completely. They have never ceased to exist, to rebel, both with weapons and with a smile, creating, living.

By the simple fact of continuing to exist as a human being in a system that dehumanizes us, we are already struggling.

Was it difficult to reconcile the work of a historian with that of your imagination as an author?

During my historical research, I have often confronted myself with what I call the silence of the archive. For example, I came across settler stories about women – African, slave or indigenous – as objects, not subjects. So I felt frustrated: I wanted their your version.

So I wanted reconstitute the voices of these silenced people from the colonial archive and official historiography. And it is there the path of imaginary creative writing imposed itself on me. The imagination has filled these holes in the archive.

To give you an emblematic example, the character of Nònoum is inspired by the dictionary written by the missionary Raymond Breton. In this work, this settler recounted an encounter with a women lad (a shaman). He says that the shaman, seeing him, went into a trance and shouted in the language of Kalinago: “Get it, I’ll kill it! Tie it up and I’ll tear it apart! “. It was then that I figured this woman had had a premonition : he started screaming because he saw what it would be the tragic history of the Kalinagos if they welcomed the settlers …

My book does not “denounce” slavery: my target audience is already aware of it. For me the key was to insist resistence rather than showing people simply victims of vile violence.

In the book you manage to describe the violence and perniciousness of the slave system without falling into the exhibition of the suffering of racialized people and trauma porn …

It’s a lot difficult to write about a crime against humanity. How to represent such a vile, immense and almost unimaginable crime in terms of violence and horror? Not including scenes of violence would have been a lack of respect and realism.

But at the same time, I didn’t want to go too far in this play out of respect for the victims of this violence. It was not necessary to pour in traumatic pornographythat is an aestheticization of the violence of racialized peoplefinally returning to the permanent reproduction of this suffering. Under the pretext of “denouncing”, we show violence in a very crude way : but who still needs to be convinced of the violence of slavery and colonization ? My book does not “denounce” slavery: my target audience is already aware of it. For me the key was to insist resistence rather than showing people simply victims of vile violence.

I wanted to instill in them a message of hope because as young people of this history of colonization that continues to combine with the present, we can feel overwhelmed and helpless

Also pay a hopeful tribute to contemporary young activists …

Yes, it was very important to me. This book is too a love letter to young people who are active and struggling today. I am thinking in particular of those who are extremely censored because they dismantle the statues of the slavers or denounce the poisoning with chlordecone.

I wanted to instill in them a message of hope because as young people of this history of colonization that continues to combine with the present, we can feel overwhelmed and helpless. These the battles are heavy to bear. But I wanted to show that you can also see them through a prism of beauty, love and sisterhood.

In the book, love and beauty are as present as the struggle …

I wanted to celebrate the beauty of our struggles, but also of our humanity, which is not limited to the fight. Sometimes we are so caught up in this struggle that we find ourselves to define our whole existence as a struggle versus : versus the racism attributed to us, versus capitalism that destroys us, versus the patriarchy … Finally, our existence ends up shrinking.

In my opinion, it can be the worst crime of these domain systems. We are deprived of the right to be only human beings, as well as the right to be frivolous. We have no choice but to direct our entire existence towards the struggle to dismantle this system. Sometimes some of us won’t be able to fight head-on. But the simple fact that these people they continue to live, to transmit their culture, to show sisterhood and solidarity, it is already a struggle. For the simple fact of continuing to exist as a human being in a system that dehumanizes us, we are already fighting.

Featured image credit: © Madmoizelle

Source: Madmoizelle

Ashley Root is an author and celebrity journalist who writes for The Fashion Vibes. With a keen eye for all things celebrity, Ashley is always up-to-date on the latest gossip and trends in the world of entertainment.