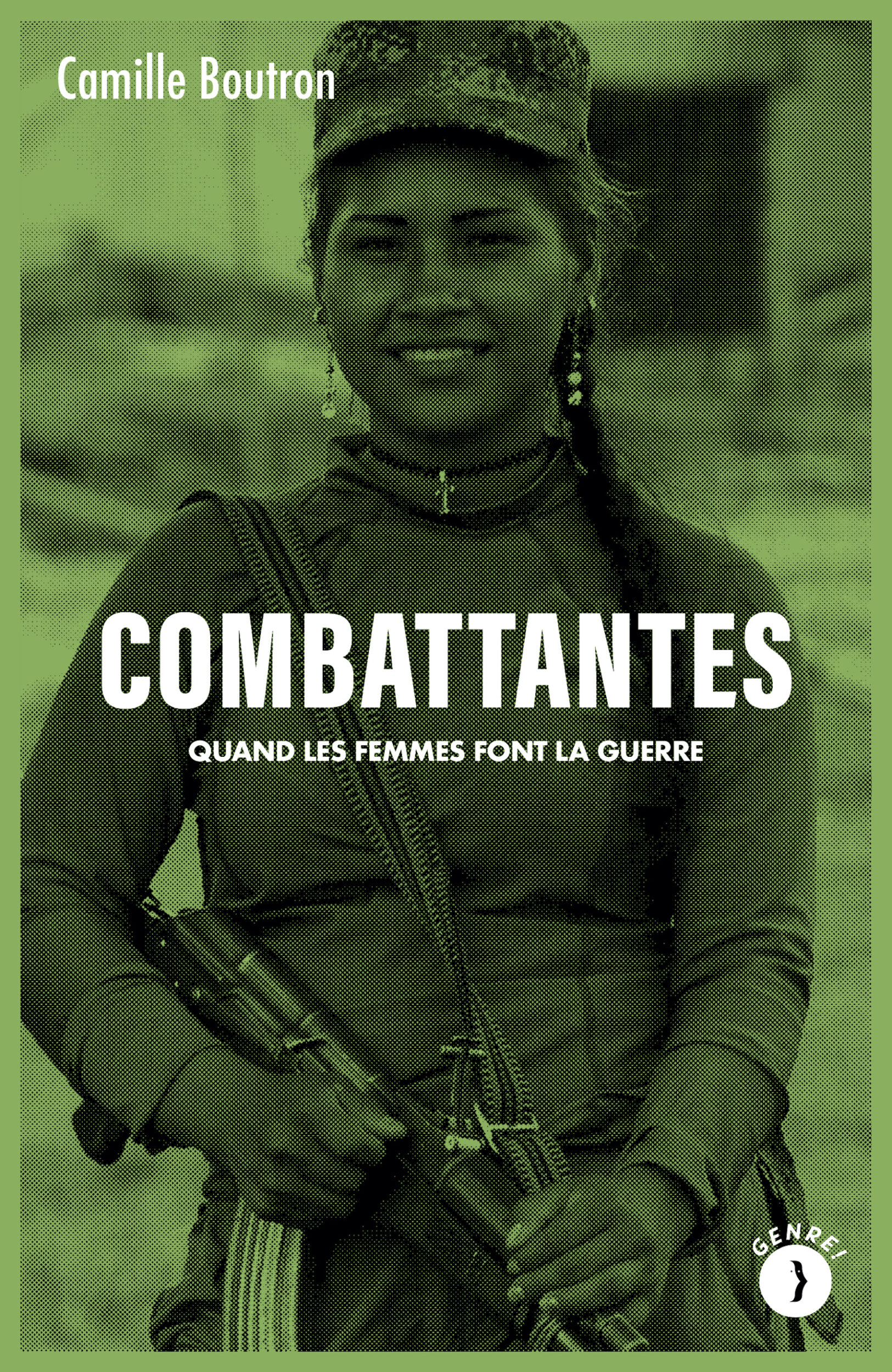

Women and war. By combining these two words, stereotypes flourish. The first image that comes to mind is certainly that of wives, mothers and girls, victims of savage wars perpetrated by men. The other is to imagine legendary female warriors, from Joan of Arc to Resistance fighters. But there is another category, even if it is a majority one: women fighters, more simply integrated into armies and guerrillas. A sociologist by training, Camille Boutron has made armed conflicts in South America and the place of women in this world her favorite topics. After her thesis on the role of women in the Shining Path (Communist Party of Peru), her research continued in Bogota, Colombia, where she worked as a teacher-researcher. After twelve years in South America and a new assignment at the Military School’s Strategic Research Institute, the researcher expanded her work to France. Result? Female fightersbook published on March 22 by Les Pérégrines, in which Camille Boutron contextualizes the place of women in war, freeing herself from an essentialist gaze.

To miss. You immediately say that talking about “female fighters” can sometimes be problematic. For what ?

Camille Boutron. We never talk about it“fighting men”. We talk about “fighters” in an armed conflict because we have a gendered approach towards the combatant actor. Talking about “female fighters” was like opening a black box. It was necessary to deconstruct the polarity that we always hear this way “Women are the main victims of armed conflicts”the idea of “woman victim/man fighter” and put into perspective the archetypal representation we have of the world of war.

Why are women always seen as victims of war or glorified fighters, and never as fighters on the same level as men?

There have always been women fighters. We tend to talk about them as if they were heroines, but we will not enthuse about the case of Inès Madani, the origin of the failed attack on Notre-Dame-de-Paris. Access to combat, to weapons, to political violence, is a way to maintain social hierarchies and male dominance. So keeping women away from fighting means keeping them away from the spheres of power. Speak about “women fighters” shows that war is one of the tools that allow the maintenance of patriarchy. We quickly realize that political conflict is a reflection of private conflict. I think we need to talk about it “fighter experience” because arguing is just a moment in a woman’s life.

Are the reasons for women’s commitment different from those of men?

I do not think so. There are many ways to find yourself in an armed group. First, being forcibly recruited. Then it can be a rational choice, because we have nothing better to do. I saw it in interviews in Peru: very young women who found themselves in such intensely precarious situations felt that following the group was no worse. Finally, there are real reasons. I think what motivates us to embrace violence is very internal. And I’m not sure it has a gender. On the other hand, military careers are necessarily influenced by gender and women do not become war leaders.

You have mainly done fieldwork in South America. How is this continent representative of women fighters?

In Latin America, decolonization occurred well before Africa and Asia, so we established states. Each country had its own little guerrilla war in the 60s and 70s. The use of weapons is necessary because it is seen as the only way to achieve political transformation. It is contemporary with the second wave of feminism. In this historical context there is female political commitment. The particular case of Shining Path in Peru really contributed to the development of the women’s recruitment strategy.

There is also the particular case of the FARC fighters in Colombia.

This is an exceptional guerrilla force, active for fifty years, always with many women. Daily activities are very shared. On the other hand, at the higher hierarchical level, there are no women. During the peace negotiations, supported and financed by international cooperation, with mediating countries such as Norway (this is important because gender issues are essential for these Nordic countries), women were put forward on the international stage. At that time, in 2012, there was a very organized movement of civil society women in Colombia. But there are no women in government. There are some in the peace delegations, but not in the decision-making group. So the FARC women decided to take advantage of this situation. They managed to reclaim their revolutionary past by integrating it into a feminist mobilization. They have built their own feminism, “rebel feminism”, explaining that they are so feminist that they have made the revolution. The movement has continued since then.

Read also: From writing to self-defense: when feminist anger gain territory

What happens to veterans?

Returning from war is complicated for women, but it depends on the case. I have not done any field research in Africa, but I know that in Eritrea women fighters are no longer considered eligible because they have lived mixed with men and slept with them. In Latin America it is different. In Colombia, women fighters are often asked to become women again, to have children, to return to professional activities related to them “treatment”. By regaining their place as women, they become more precarious again. Peace is achieved through the prism of the reconstruction of gender identities as we know them to reassure everyone. However, female solidarity can be created between them.

Can we link participation in war to women’s empowerment?

I don’t think access to combat is a vector of emancipation. It is precisely because women organize themselves to demand equality and become politically engaged that they represent added value for the guerrilla. Women are an added value, not a conflict.

What about the place of women in the French army today?

There is a real paradox in the French army which is quite feminised. General Anne-Cécile Ortemann, director of the Defense Digital Agency, has worked hard for diversity. There are about 16% women, with an effort in recent years to increase the number of women in the senior officer corps (we are approaching 10% female generals). But there are few women in the field in ultra-combat operations, even though having fought is very important to rise in rank. Until this culture is challenged, the face of war will not change.

Do you think conflicts would take different directions if there were more women in decision-making positions?

For sure. The idea is not to say that putting women in these positions would change things because they are women, for biological reasons, but because the women who arrive in these positions have faced challenges, obstacles, which are, at some point, dictated from the genre. They are necessarily constructed differently. This difference is an asset.

Are war and feminism compatible?

NO. Violence and feminism perhaps, because violence is inherent in social relationships. We must not be afraid of this term “violence”. This is what I try to explain a little at the end of my book. I also recommend reading Elsa Dorlin’s book, Defending oneself: a philosophy of violence.

You evoke the fate of many women fighters who arouse admiration. Which one particularly moved you?

There are many. Everyone I meet shocks me. But I want to talk about Milagros, a fighter from the MRTA (Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement). I spent a lot of time with her in prison. She left five or six years ago. She studied at university, she is bright, lively. She had her life ahead of her, but her involvement with the MRTA ruined her. She doesn’t regret anything, but I can’t help but tell myself that the world is doing well so that these women are harmless and don’t go so far as to question the dominant system.

Female fighters. When women go to war by Camille Boutron, Les Pérégrines editions, 296 pages, 20 euros. In bookstores from March 22nd.

Add Madmoizelle to your favorites on Google News so you don’t miss any of our articles!

Source: Madmoizelle

Mary Crossley is an author at “The Fashion Vibes”. She is a seasoned journalist who is dedicated to delivering the latest news to her readers. With a keen sense of what’s important, Mary covers a wide range of topics, from politics to lifestyle and everything in between.