After filming her paternal grandparents, Algerians who have lived in Auvergne for 60 years, the originally French director Lina Soualem, Palestinian-Algerian facing women of his family, taking inspiration from the story of his mother, the Palestinian actress Hiam Abass. Even if it only lasts an hour and twenty minutes, Bye bye Tiberias East an extraordinarily rich film. The diversity of what is shown to us on the screen is the image of this thematic, political, artistic and emotional abyss.

The film flows in between personal archives of the 90s. Weddings, evenings on the terrace, afternoons at home where we see more people living together generations of women – a mother, a grandmother, sisters. Among these, Lina, a very young girl. There are also images, extremely precious and difficult to find on a global scale the Nakba (in Arabic, “the catastrophe,” which refers to the forced exile of the Palestinians in 1948).

And then there are the images created for the film: Lina Soualem filming her mother, the actress Hiam Abbass. Only Abbass appears as the personification of a Palestinian story, of womanhood and of this rich film. She is both an actress and performs in front of Lina’s camera. She recites poetry, she stages a scene from her youth on the stage of an empty theater. But, in most cases, Hiam is above all a woman full of nostalgia, regrets, contradictions, wounds but also with irresistible humorFrom prideFrom determination and love for his land, his mother, his grandmother, his daughter.

“I thought my mother did it he was shaped by his life of exile but in making this film, I understood that all its values, its culture, its light, its richness were already there, in Palestine, thanks and with all these other women. »

Lina Soualem, during the film’s premiere at the Meliès cinema in Montreuil.

The voiceover, concise and brilliantly written, weaves a thread this ambitious story, which leaves no one behind. The goal is not to paint a portrait of a Palestinian icon but to do it show the collective story of women with strength, culture, values and love of incredible richness. With a story with sincerity and authenticity which does not emerge unscathed (when the lights come back on, the audience has red eyes), Lina Soualem breaks the stereotypes that hover over the Palestinians, who see themselves systematically reduced to the death toll, a conflict “too difficult to understand”or even monsters.

Meeting with Lina Soualem

To miss. What did you want to achieve with this film which, while delving into the intimacy of the women in your family, repairs a present corrupted by stereotypes about Palestinians?

Lina Soualem. In Their Algeria as in Bye bye Tiberias, I wanted to film the intimate story of my family. But it wasn’t just about telling their personal story because they seemed unique to me, on the contrary. I felt that their story each time echoed a more collective story.

These are people whose stories did not exist in public space or who were represented in a stigmatized way Algerian immigration to France which is represented as if it were a story foreign to the French one. It’s the same thing for Palestinians who are always represented as abstractions or figures, death matters. They suffer very strong dehumanization.

I wanted to highlight the individuality of their family members because their story is fascinating. Despite dispossession, exile and uprooting, they managed to build and transmit strong and luminous things and values. Capturing their memory is not just for me. It’s about making them exist in public space and enriching the representations.

We often hear that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is “too complicated to understand,” using it as a pretext to obscure or deny Palestinian identity, its culture, its greatness, its heritage and its suffering. You push back against this rhetoric, while making a film that remains challenging and historically rigorous.

Yes is complicated because the territory is fragmented, and history is not linear because it has been obscured, silenced. There was a whole moment where the word Palestine was banned Families have been broken up, so the transmission is made up of breakups and separations. So obviously it’s complicated for us too to tell stories. It’s like the history of French colonization in Algeria which is a history full of holes, gaps in memory, taboos. There is silence in families.

On the other hand, it’s not complicated to understand that there are situations of injusticepeople who suffer displaced, deprived of their rights, their family, their identity. No one can deny these facts.

On the other hand, being able to do it transmit what they experienced, we must do a writing job so thatthey can exist in their most complete humanity, in their strength, in their vulnerability, in their doubts, in their contradictions. They are far from being the homogeneous and abstract block to which they are reduced. I will quote Karim Kattan who wrote a magnificent text nominated Gaza is not an abstraction, in which he explains that Gaza is alleys, markets, people who have dreams, aspirations, emotions of lives. Having to remind people of this is terrible, but it is necessary because of dehumanization.

During a discussion about your film after the screening, Alice Diop said of your film “We are the fruit of a silence, of an absence of memory. It makes us want to archive, to record our memories. Only we can do it.”

Like Alice Diop, or other artists like Faïza Guène, I understood what I felt the need to tell our stories in our own wordsto no longer be perceived by those who stigmatize us.

There is a need to actualize our complexity, since it is denied to us. Dehumanizing, essentializing, means rejecting this complexity.

We want to tell each other about our first, second or third generation experience. Mixing our intimate struggle as women with what we collectively experience. Because we come from torn histories colonization, forced exile, war, we are often perceived through the gaze of the oppressor.

Our own words, our own sensations become a new language.

While making the film, I understood this too the history of the women in my family had to pass through my pen and my words to give back to all these women the strength of their history. Because it’s almost as if telling it head-on on camera doesn’t give the full picture. the epic dimension, sensory, poetic, all the strength and harshness of what they experienced. I needed to uplift and give back to these women all the imagination they deserve and have perpetuated for their descendants as well.

No more going through pre-constructed perceptions and affirming something that belongs to us it allows others to find their place in the world. Tell them that they too can create their own language to define themselves outside of anything imposed. For example, I was very happy when during a preview two young people, a Congolese and a Senegalese, told me that my film had made them want to make a film about their mother and their family.

Recently, we have seen the emergence of many collectives of North African, Arab and Afro-descendant origins coming together to do this work of writing their history and identity. For example, are you part of the Arabengers collective or the Rawiyat collective of North African and diaspora filmmakers…

It is quite difficult to analyze because it is a very contemporary phenomenon, which is happening currently. I talked about it a lot with Faïza Guène while I was writing the series Oussekine. In her time, there weren’t many women doing this work around her. Today is different, I have examples I can count on and draw inspiration from. There are also all these groups, these communities that come together through reflections, a common language that we explore together. There is also Vintage Arab, which works on the legacy of North African music. It’s exciting, we feel transported by a whole that reconnects us to all those who existed before us.

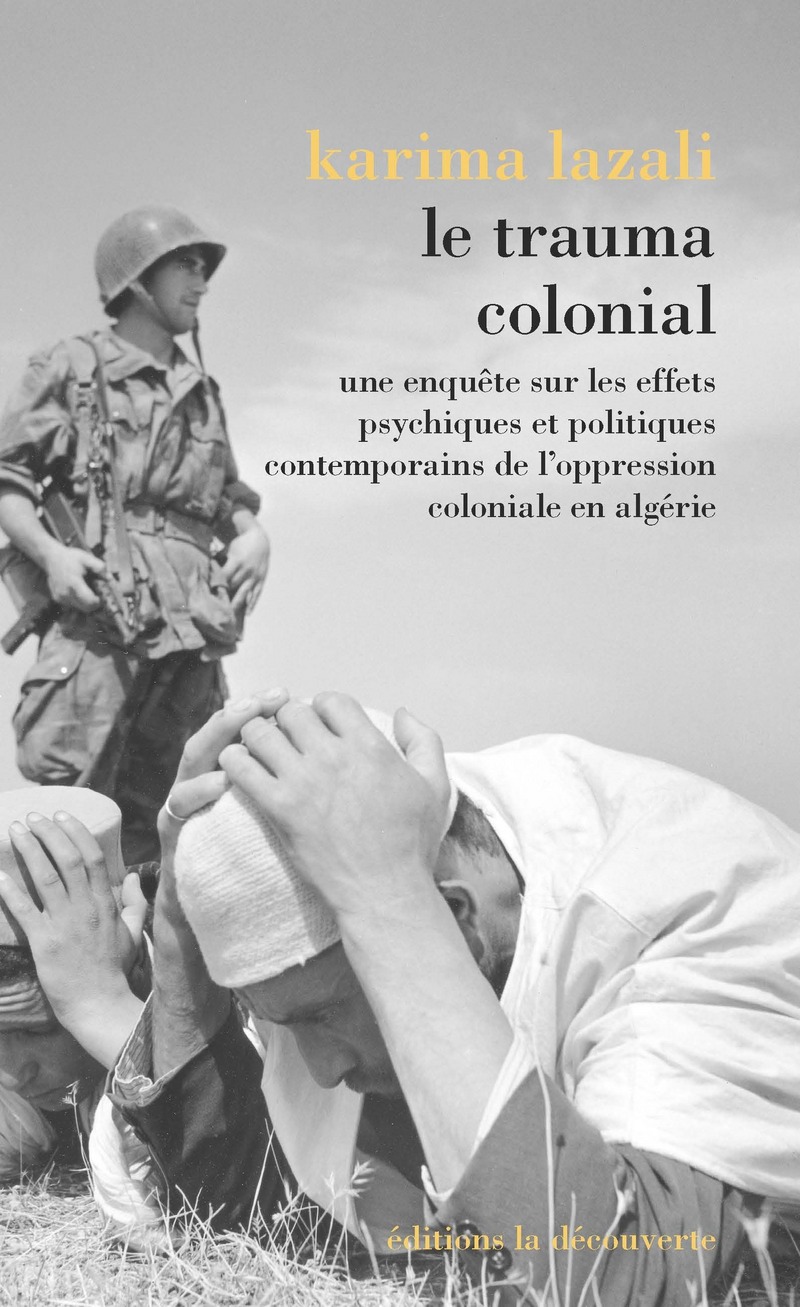

I have the impression that when I make my films, I am lucky to be in a moment in which many women speak openly, they want to tell their stories with their words, their sensitivity and with their strength, their freedom, their their legacy. They also affirm their identity as women, accepting and analyzing the fact that they are torn between different places, different cultures. As mentioned Karima Lazali who wrote Colonial trauma, we accept that we are born in an intermediate space, since neither entirely there nor entirely here. This intermediate space is the space of margin, but which we want to put back at the center. This is a bit of thatEdward said he wrote about exile: it generates sadness, regret, it is a human tragedy. But it is also a way to reinvent yourself, to find a place spaces that do not exist for us but that we will create.

Do you like our articles? You’ll love our podcasts. All our series, urgently listen to here.

Source: Madmoizelle

Mary Crossley is an author at “The Fashion Vibes”. She is a seasoned journalist who is dedicated to delivering the latest news to her readers. With a keen sense of what’s important, Mary covers a wide range of topics, from politics to lifestyle and everything in between.